|

The word "ichnology" is derived from the Greek ichnites, which means a "footprint", and when Professor Edward Hitchcock (1793-1864) of Amherst College in Connecticut in 1836 began studying fossil tracks in the Connecticut River Valley, he referred to them as ichnites. He also attributed these tracks (which he later called Eubrontes) to giant, long-extinct birds, "thick-toed" and it was only after many years of debate that the Buntsandstein and Connecticut Valley trackways were reinterpreted as the traces of ancient bird-like reptiles that eventually came to be known as dinosaurs.

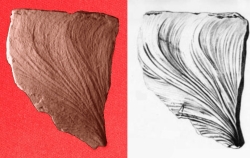

Hitchcock is considered by some to be the father of Ichnology, as he used a variant of the word in 1841 when referred to the study of fossil tracks as ichnolithology. He then followed the 1851 lead of Scottish naturalist William Jardine when shortened this to ichnology with the 1858 publication of his study on the Ichnology of New England. Hitchcock was also the first to use -ichnites and -ichnus in the suffix of trace fossil names, with his 1836 description of the tracks Ornithichnities (changed in 1845 to Eubrontes), and his 1858 description of the worm burrow Cochlichnus. As debate on the German and Connecticut trackways continued, geologists were also studying a variety of other molds and casts on the bedding surfaces of sedimentary rocks. Early French naturalists called these structures "traces physiologique" to distinguish them from body fossils such as shells and bones, whereas the Germans called these features "lebensspuren", which more of less translates to the traces (or tracks) of ancient life. French paleontologist Adolphe Brongniart (1801-1876) in 1823 published an influential paper in which he interpreted branching trace fossils as fossil impressions of a type of seaweed (brown algae) called fucoids. Brongniart's writings were popular, and geologists for the next sixty years interpreted most trace fossils as fossil fucoids.

The recognition that the burrows and tracks of soft-bodied invertebrates could be preserved in ancient sedimentary rocks was slow in coming. Although the emphasis was on a living organism, Charles Darwin's 1881 study of earthworms and their burrows was an important contribution to ichnology, as it drew attention to the fact that worms living in the soil, and by extension worms living in marine sediments as well, made extensive modifications to their environment. Alfred Gabriel Nathorst (1850-1921) and Joseph Francis James (1857-1897) in the late 1880s demonstrated that many of the "fossil fucoids" identified by their predecessors (which included Joseph's father Uriah James) were more likely to be the grazing trails and burrows of soft-bodied animals such as worms and shrimp that had neither bones nor shells to leave behind as fossils. The early twentieth century was a renaissance with regard to trace fossil study, with German geologists studying modern burrows in the tidal flats of the Wadden Sea for analoques to interpret the fossil past. There was also a great deal of emphasis on identification, and assigning as many genus and species names as possible to the many lebenspurren found in nature. However, trace fossils in many cases are difficult to impossible to assign to specific organisms, especially where the organisms had no hard parts to preseve. This means there is often no hope of finding the burrow maker preserved in its burrow. Also, the same trace may be made by several different, unrelated animals, which meant that attempts to develop an all-encompassing classification system with which to assign scientific names to these features largely met with failure. Adolf Seilacher (1925-2014) studied under and collaborated with several of the famous German sedimentologists of the early twentieth century. He ultimately wrote his 1951 Ph.D. thesis on trace fossils, and introduced a behavioral classification system that is based on the purpose for which the trace was created. He also introduced five behavioral classes - resting marks, dwelling, deposit feeding (mining), crawling and grazing - an approach that today seems more logical than assigning genus and species names. He also introduced the concept of ichnofacies, in which assemblages of trace fossils are thought to represent specific sedimentary environments. These contributions have led many to consider Seilacher the father of modern ichnology.

|

|

Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) is actually one of the first naturalists known to have studied trace fossils. He was was commissioned in the late 1400s by the Duke of Milan to work on various artisitic projects in and around the areas of Parma and Piacenza in northern Italy, where the locals would bring him interesting rocks that they found in the nearby Apennine Mountains. Some of these rocks contained stange shapes that we now know to be trace fossils. Da Vinci writes in his secret notebook the Codex Leicester that "among one and another rock layer, there are the traces of the worms that crawled in them when they were not yet dry." This indicates that he clearly understood that these traces were the burrows and crawling marks of soft-bodied animals that had neither bones nor shells to leave behind as fossils. However, de Vinci's insights were not shared with others, as his notebook was written in Italian, in mirror writing that is next to impossible to read unless reflected in a mirror. Thus, his observations had no impact whatsoever on the advancement of the science.

Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) is actually one of the first naturalists known to have studied trace fossils. He was was commissioned in the late 1400s by the Duke of Milan to work on various artisitic projects in and around the areas of Parma and Piacenza in northern Italy, where the locals would bring him interesting rocks that they found in the nearby Apennine Mountains. Some of these rocks contained stange shapes that we now know to be trace fossils. Da Vinci writes in his secret notebook the Codex Leicester that "among one and another rock layer, there are the traces of the worms that crawled in them when they were not yet dry." This indicates that he clearly understood that these traces were the burrows and crawling marks of soft-bodied animals that had neither bones nor shells to leave behind as fossils. However, de Vinci's insights were not shared with others, as his notebook was written in Italian, in mirror writing that is next to impossible to read unless reflected in a mirror. Thus, his observations had no impact whatsoever on the advancement of the science.